Are not the observers quickest to slap the label ‘syncretic’ on phenomena precisely those who are least interested in capturing ‘the native’s point of view?’ —David N. Gellner1

Rethinking syncretism is not about condoning multiple allegiances, in which one worships Christ and another god. Rather, it calls for a critical reflection on the paradigms through which we evaluate phenomena labelled as syncretistic. In this article, syncretic is used neutrally to describe the synthesis of divergent cultural elements to generate hybrid forms, whereas syncretistic carries a pejorative connotation, implying disapproval of such mixing. Here, I employ syncretistic specifically to denote a condition of the heart, in which one’s faith and devotion to Christ is divided. This article examines syncretic expressions that have been deemed as syncretistic, submitting that misjudgments not only hinder in-depth understanding of another’s culture but also undermine Christian witness.

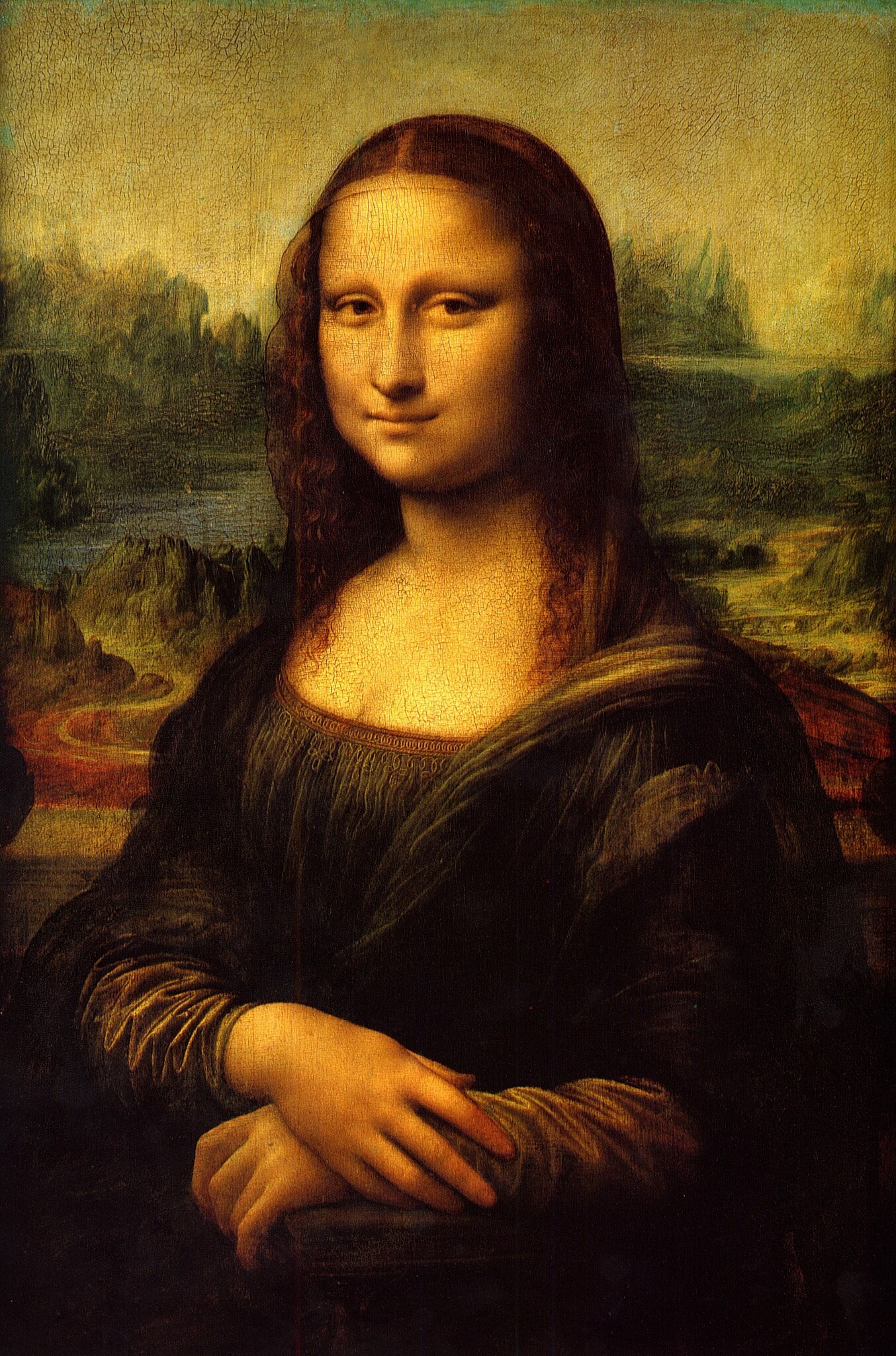

Consider the two portraits on the right.2 What do you think of the abstract piece?

If we were to assess it using Leonardo da Vinci’s artistic techniques, we might consider the former as substandard—lacking proportion, three-dimensionality, and lifelikeness. However, such a judgment tells us more about the evaluative framework of the observer than the artwork itself. How we appraise depends on the parameters we use.

Now, consider these three religious phenomena below.3 What do you think of them?

Many Westernized4 outside observers have described such mixing of religious elements as syncretistic. This assessment presupposes a definition of religion as a pristine and mutually exclusive system of beliefs and practices, and that intermingling from different religions amounts to corruption and illegitimacy. However, as repeatedly noted by various anthropologists,5 the adherents themselves do not self-consciously draw boundaries between traditions nor see their practice as improper. Does this mean that the local people have a lapse of rationality? Or, does the dissonance point to a different logic and conceptual framework of “religion?” Employing a social science methodology, Samuel Perry contends in Religion for Realists that the conception of religion is not monolithic. Here, I focus on Southeast Asian Theravada Buddhism as a “religion” and show how an emic (internal) frame of reference can produce a less disparaging view of another culture’s way of life.

Religion: A Contested Category

Indeed, several anthropologists who have studied non-Western societies, have maintained that religion is an “essentially contested category.”6 Let me explain this by way of an analogy.

What is a tomato—a vegetable or a fruit? According to scientific classification, tomatoes are fruit because they grow out of flowers and have seeds. However, they are legally classified as a vegetable in the USA. In 1893, the US government had imposed a tariff on imported vegetables, but a certain importer argued that tomatoes are fruit and refused to pay the taxes. However, the Supreme Court ruled against him, explaining that tomatoes may be fruit in the textbooks but in everyday culinary practices, they are consumed as a vegetable. So, is tomato a vegetable or fruit? It really depends on who decides. Tomato is thus an essentially contested category.

Similarly, what is religion? It really depends on who decides what the defining parameters are.

In modern Western societies, religion is a discrete, coherent system of hermeneutically derived doctrinal beliefs and scripturally aligned practices. This historical construct emerged out of the departure from Roman Catholicism during the Reformation and a struggle against secularist rationality during the European Enlightenment. The separation of Church and State, which grew out of the secularization movement, was particularly expedient for the colonial enterprise to displace the traditional power structures of their colonies. Relegating religions as personal faiths in private worlds dismantled the indigenous relationship between religion and statecraft.

However, in non-Western civilizations, religion was not even a word in pre-colonial vocabularies; the words for religion in different Asian languages today are borrowed and modified or neologized. In Khmer, sasna in an 1878 dictionary was interchangeably translated into French as religion or race. Etymologically, it is derived from the Pali word sāsana which refers to the teachings—in this case of the Buddha—to be practiced, which form distinct characteristics of a race. In Myanmar, batha, which is derived from the Pali word bhāsā, meaning language or academic subject, was extended to refer to religion during the British rule. In Sinhalese, agama originally referred to things that were passed down through many generations, such as traditions or sacred texts. In Chinese and Japanese, the terms zong jiao and shokyu were neologized because of the need to compose Memorandums of Understanding with Westerners. Before the encounter with the West, religion was not dichotomized from the life of a society. A people’s way of existence is based on sacred wisdom—traditional knowledge including “religious” teachings—passed down through generations. Life and society are inherently religious.

This non-dualistic understanding of a religious socio-political life was challenged during the colonial period when the British and French powers and American expansionists sought to modernize Burma, Indochine, and Siam through Western secularist ideologies. The local people, however, rejected such impositions. Instead, they turned to the sāsana and drew on its wisdom as a resource to rearticulate their identities, assert cultural sovereignty, and envision a religiously imbued, modern “nation-state.”7 The colonial encounter awakened a distinct Buddhist consciousness, and Buddhist nationalism arose as a resisting force against Western hegemony. Unlike the Western construct of religion, which emerged from internal conflict, the Theravada Southeast Asian conception of religion was forged in the struggle against external domination. The relationship between religion, culture, identity, and polity, which already existed in the pre-colonial era, became cemented.

This construal of “religion” is thus situated largely within the social domain, intimately intertwined with tradition, community, belonging, and identity, rather than scriptural texts and doctrinal beliefs. As the eminent Buddhist scholar, Richard Gombrich, comments, the Buddhism that was imagined by foreign academics intrigued by Pali texts is but a philosophical abstraction; lived Buddhism, by contrast, is a matter of group loyalty and national interest—“the social allegiance appears to be the true determinant of action and the religious language to be an obfuscation, the question of orthodoxy or orthopraxy a mere epiphenomenon [i.e. secondary by-product].”8

This analysis concurs with some dimensions of Perry’s characterization of religion in reality. In Theravada Southeast Asia, religion does not primarily revolve around trans-national doctrinal beliefs but localized identities and belonging; it is not so much a personal faith as public practice; its locus does not lie in texts and the cognitive mind but in relational practices and inter-acting bodies.

This raises a crucial question: With differing conceptions of religion, whose framework do we use when examining other cultures’ practices of life?

Re-examining Religious Blending Through a Non-Dualistic Paradigm

When Westernized observers encounter religious practices composed of seemingly disparate elements from different traditions, we instinctively label them as syncretistic. Such judgments presuppose the existence of “pure” faiths, without realizing that Christianity itself is profoundly syncretic, with associations to many pagan practices.9 The very concept of “world religions,” formulated in the 19th century, emerged largely from academic abstractions from texts rather than lived practices. This codification of religions reflects the broader scientific penchant for classification—differentiating things according to select criteria and grouping them within rigid boundaries. When this caricatured framework of religion is employed to analyze lived realities, numerous expressions fail to fit the textual mold—much like forcing a square peg into a round hole. Practices that do not align neatly are then dismissed as aberrations. Yet, if we adjust our lens and examine the same phenomena through different logics, the picture changes—like viewing stereograms through a different optical vergence. In the following paragraphs, I suggest how religious blending may be reinterpreted through a different paradigm.

As Shaw and Stewart have seminally shown, the religiously charged language of syncretism often obscures the socio-political dynamics in which such practices emerge.10 Their study on the politics of religious synthesis highlights the importance to attend to the power dynamics underlying religious amalgamations and discourses. For example, the Harihara of Cambodia was not so much a blending of two religions as a calculated political strategy.11 The hybrid Shiva-Vishnu image, which proliferated during the Zhenla period after the collapse of the Funan dynasty, served to unify rival sects and vassal states within a newly consolidated mandala. As religion, ethnicity, and statecraft were deeply entwined, Harihara was an emblem of a new polity. Similarly, the syncretic iconography of Buddhist and Hindu motifs represented “multivalent symbols” that were often deployed to be “all things to all people” in multi-religious contexts.12 What appears as religious syncretism may in fact be political expediency rather than theological compromise. However, the notion of political expediency carries negative connotations and subtly reinforces the sacred-secular dichotomy—that rulers cunningly manipulate religion for political ends. Within a Buddhist framework, such actions may instead be understood through a non-dualistic moral logic.

In Theravada worlds, the dhammarāja or righteous king is guided by an ancient moral code called the Dasarajadhamma (Ten Royal Virtues), which includes maddava (being kind and approachable), ahimsā (exercising non-violence), and avirodha (respecting diverse opinions). From this perspective, “syncretistic” behaviors may be reinterpreted as expressions of inclusiveness and promoting peace. As Peter Van der Veer suggests, syncretism need not signify impurity or heterodoxy but can belong to a discourse on communal harmony.13 In societies where cohesion and stability are prioritized, doctrinal exclusivity is not the logic that drives and governs action.

Another Buddhist principle—upaya (skillfulness or adeptness)—may further reframe “syncretistic” practices. Originally describing the Buddha’s ability to adapt his teachings to his audience’s understanding, upaya, in the context of statecraft, refers to how dhammarājas skillfully engage with diverse polities—preserving peace and advancing prosperity, without undermining the distinctiveness of respective ethnoreligious communities. As Julia Esteve contends, when a king supports diverse religious establishments or incorporates their sacred wisdom into his governance, these acts do not reflect his personal faith but his impartial and magnanimous support of the diverse populations within his realm.14 Within this interpretive framework, pluralism rather than syncretism better captures the ethos of these actions.

This Buddhist ethic of inclusivity and skillful discernment extends beyond human relations to the world of spirits. Buddhists routinely make offerings to ancestral, tutelary, and wandering hungry spirits, as well as Hindu deities such as Vishnu or Ganesh. While such acts are deemed as syncretistic from a Western standpoint, practitioners do not self-consciously see themselves as violating their own religious identities. How might we understand this?

In the Buddhist worldview, spirits, humans, and animals all belong to the same “scientific” category called satta (sentient beings). Spirits are just another life-form within a unified socio-cosmological universe, who should be treated with common decency, respect, and compassion. A person who offers a gift to a territorial guardian is no stranger than one who offers a gift to his village chief in order to seek a favor. To feed a hungry spirit is no stranger than feeding a stray dog—these are acts of compassion. As taught in the Lovingkindness Sutta, goodwill is extended to all beings (sabbe satta sukhi hontu).

This non-dualistic worldview reshapes the way human-spirit interactions are understood. When Buddhists offer gifts to Hindu deities or tutelary spirits, these acts need not signify faith allegiance, and thus do not necessarily constitute polytheistic worship, in the Christian sense. Unlike the Christian’s personal and exclusive relationship with God, the nature of the human-spirit relations in a moral cosmos is discernibly distinct—transactional yet ethical, not as endearing disciples of a deity. A man wishing to clear the shrubs in the backyard to build a shed would respectfully inform the spirits through ritual offerings. A woman visiting Angkor Wat would present flowers and incense before a Vishnu statue to honor his historical role in the Angkor Empire.

Deities and spirits—benevolent or malevolent—are not necessarily worshipped as personal gods; Cambodians do not pledge fidelity to them as Christians do to God. Human-spirit interactions are not framed as monogamous relationships but multivalent patron-client exchanges, akin to patron-client human-human networks. In Khmer, the word preah (“god”) is also understood as an adjective referring to a superlative quality.15 Spirits or “gods” are thus just supranatural beings within a hierarchical cosmology, and are treated accordingly with appropriate decorum. This dynamic does not preclude the possibility of humans forming enduring commitments with particular spirits, which would then be tantamount to idolatry—no less than being consumed by worldly possessions or ambitions. As counterintuitive as this is to monotheist sensibilities, within this holistic imaginaire of the universe, enactments of gift-giving and reciprocal exchange are conceived in social rather than religious categories, as gestures of propriety rather than reified acts of sacrifice.

More Robust Critique of “Syncretism”

This article is written from an anthropological perspective, offering a more nuanced and compassionate view of other peoples’ ways of life through emic paradigms. Paul Hiebert, renowned for his work on critical contextualization, recom-mends us, first of all, to study local cultures phenomenologically. Central to the philosophical school of phenomenology is the reflexive examination of our assumptions and biases and the empathic understanding of cultural phenomena through indigenous logics rather than external critique. In this spirit, I have sought to reframe religious assimilations, or what we often call “syncretism,” through an emic conception of lived religion, in which religion and culture as well as earth-ly and cosmological worlds form a seamless whole. Instead of viewing religions as competitive systems, they might be considered as sacred wisdoms of civilizations, bearing traces of God’s image and truth. Rather than dismissing mixtures as incoherent and illegitimate, they might be moral expressions of magnanimity, harmony, and astuteness. Additionally, reading cultural phenomena through indigenous paradigms may help remedy what Hiebert calls “the flaw of the excluded middle”—a cognitive gap prevalent among people with a “two-tiered view of reality” who dichotomize reality into rigidly separated spheres.16

Understandably, for those shaped by monotheistic and European Enlightenment traditions, any sympathetic analysis of “syncretism” naturally provokes uneasiness.17 To be sure, this essay is not intended to compromise the gospel’s integrity. On the contrary, it seeks to enhance Christian witness by remedying our disparaging views of others and abrasive mission approaches, that are increasingly problematic in our 21st century world, which is multipolar and intercultural. By reflexively examining the interpretive frameworks we use to study other cultures, we may cultivate a more nuanced and in-depth understanding, as well as a more respectful and compassionate response toward non-Christian religious cultures. The abstract portrait is a work of Pablo Picasso, which was sold for $103.4 million at Christie’s auction.18

1 David N. Gellner, “For Syncretism: The Position of Buddhism in Nepal and Japan Compared,” Social Anthropology 5, no.3 (1997): 277–291.

2 Pictures are taken from Wikimedia Commons: The abstract painting is by Dagaw, accessible at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Portrait_ paintings&filefrom=Sir+John+Evelyn+of+Wotton+2nd+Bt+MP.jpg#/media/ File:Sjalvportratt_2014.jpg. Mona Lisa is accessible at: upload.wikimedia.org/ wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Mona_Lisa.jpg/1354px-Mona_Lisa.jpg

3 Pictures are taken from Wikimedia Commons: Harihara is accessible at commons. wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vishnu_and_Shiva_in_a_combined_form,_as_%22Hari-hara,%22.jpg. The monk’s blessing is accessible at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Ban_Huahat05.jpg. The Golden Window is accessible at: commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Golden_window,_Patan_Museum,_Patan_Durbar_Square1.jpg.

4 This term does not refer to just Westerners but includes non-Westerners who have been largely influenced by the European Enlightenment intellectual tradition through education and media.

5 e.g. Richard F. Gombrich, “Sinhalese Buddhism—Orthodox or Syncretistic?” in Buddhist Precept and Practice (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 47–66; McGovern, Robert. Holy Things: The Genealogy of the Sacred in Thai Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024).

6 W.B. Gallie, “Essentially Contested Concepts,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56 (1955): 167–198.

7 It should be noted that the geopolitical notion of “nation-states” had not existed prior to the colonial era, as ancient mandala polities were envisioned as a conglomeration of shifting kingdoms affiliated through tributary practices.

8 Gombrich, Richard F. Buddhist Precept and Practice (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 59; Gombrich, Richard F. Theravada Buddhism (London: Routledge, 1988), 15.

9 e.g., Viola, Frank and George Barna. Pagan Christianity: Exploring the Roots of Our Church Practices (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2010).

10 Stewart, Charles and Rosalind Shaw (eds). Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis (London: Routledge, 1994).

11 Paul A. Lavy, “As in Heaven, So on Earth: The Politics of Visnu, Siva and Harihara Images in Pre-Angkorian Khmer Civilization,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 34, no.1 (2003): 21–39.

12 See footnote 1.

13 Peter Van der Veer, “Syncretism, Multiculturalism and the Discourse of Tolerance,” in Charles Stewart and Rosalind Shaw (eds) Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis (London: Routledge, 1994), 185–199.

14 Julia Esteve, “Gods and Temples: The Nature(s) of Angkorian Religion,” in Mitch Hendrickson, Miriam T. Stark and Damian Evans (eds) The Angkorian World (London:Routledge, 2023), 423–434.

15 e.g. The moon (preah zhan) is the brightest light at night, and monks (preah song) are the best models of morality.

16 Paul G. Hiebert, “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle” Missiology 10, no.1 (1982): 35–47.

17 Tippett, Alan R. Slippery Paths in the Darkness: Papers of Syncretism: 1965–1988 (Pasadena, CA: Willian Carey Library, 2014).

18 economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/picassos-painting-of-french-lover-sells-for-over-100-mn-at-auction/articleshow/82653745. cms?from=mdr.

Author

CLAIRE TC CHONG

Claire TC Chong (PhD OCMS) lived in Cambodia for 15 years. She is presently a research and training associate with the Singapore Center for Global Missions and a research tutor for Fuller Seminary’s Doctor of Global Leadership program.

Subscribe to Mission Frontiers

Please consider supporting Mission Frontiers by donating.

Subscribe to our Digital Newsletter and be notified when each new issue is published!