Today, 97% of the remaining Frontier People Groups are either Muslims or caste Hindus—people groups who identify strongly with major world religions of at least 1 billion adherents. These “FPG” people groups from formidable religious blocs have no known movements to Christ and 1% or less Christians of any kind. They have either been bypassed by mission workers or have repeatedly rejected historical attempts to reach them.1

Is the goal to somehow get individuals or families from these FPG groups to be so attracted to a fellowship of Christian believers from a different people group that they leave their own families and communities to join fellowships in the other group? No! Donald McGavran pointed out long ago that whenever this method of attractional extraction has been used historically, such as in mission compounds, it has ultimately failed to implant the Gospel into the “dough” of the original people group. There is a 200-year history of failure of this methodology in places like South Asia.

When a people group is associated with a global religion, like Islam or Hinduism, the people becoming believers are almost always ostracized by their families and encouraged by mission workers to leave their communities to join churches in a different people group. If the church they join is made up of former strangers from multiple people groups, sometimes called “aggregate churches,” the church frequently falters and collapses under the weight of all the deep and complex functions normally fulfilled by the extended family and whole society. The believers end up in “no man’s land” where the fabric of belonging has been torn, and they no longer “belong” anywhere.

This practice is the exact opposite of the way we see Jesus and the apostles spread the good news to people from other religious groups in the New Testament. We need to get away from a “war of religions” perspective, where we are trying to make our religion or religious groups more attractive than the other religions. Instead, we need to implant the gospel into the households following the example of Jesus and the apostles.

The Good News is a Message, not a Religion

The gospel is a message that enters and transforms existing people groups, even those associated with pagan practices and other religions. Ralph Winter pointed out “the churches are already there, they just don’t know Jesus yet” meaning the familial and societal structures remain intact as the good news takes root within them. We have seen this work countless times in tribes all over the world, including our own ancestors, who can tell you when the gospel came to our own people. It also is the way to implant the gospel into people groups with strong religious identities.

Jesus showed us the way to approach people in other religions when he spoke to the Samaritan woman in John 4. She immediately pointed out that she belonged to a different religion. (And John emphasized that Jews did not associate with Samaritans.) But Jesus bypassed religious arguments by clarifying that God is spirit and is seeking all those who will worship him in spirit and truth (verses 23–24). Then he did the unthinkable by going into the Samaritan village (without the Jewish disciples) and eating and fellowshipping with them for two days. The Samaritan villagers realized that Jesus was for their community also, and was “the savior of the world,” not just of the Jews (verse 42). Jesus consistently took his message to distinct religious groups instead of extracting believers out from them. Even when the demoniac became a believer and wanted to join the disciples, Jesus sent him back home to witness to his own community (Mark 5:18–19).

Peter showed us the way to bring the gospel into the household of another religious group when God challenged him to overcome his aversion to the Roman socio-religious mega group and sent him to a Roman military family (Acts 10). After making sure they understood that he had never even entered a Roman home before, Peter said, “Now I realize how true

it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right.” He then shares the gospel message—the whole story of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection—concluding with “Everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name” (Acts10:34,43). At that point, Peter saw the Holy Spirit fall upon the whole extended household.

A turning point in history came because of Peter’s vision and experience with Cornelius’ household. God prepared him to be a witness of God’s grace to those in other religious contexts during the crucial council of apostles in Acts 15:7–11 saying: “Brothers, you know that some time ago God made a choice among you that the Gentiles might hear from my lips the message of the gospel and believe. God, who knows the heart, showed that he accepted them by giving the Holy Spirit to them, just as he did to us. He did not discriminate between us and them, for he purified their hearts by faith… We believe it is through the grace of our Lord Jesus that we are saved, just as they are.” As a result of his testimony, the apostles decided in Acts 15 to “not make it difficult” for people coming to faith in other religious contexts, setting very minimal religious rules for them.

There is no indication that Cornelius’ family was asked to leave their Roman military community to become Jews, regardless of how religious their people group was. Beginning in 27 BC, the Roman emperor had demanded that he be worshiped by his citizens. This rule lasted for about 300 years, and many Roman Christians were persecuted or killed because of it. Yet those Romans who received the good news of Jesus’ atoning death and resurrection did not have to renounce their Roman citizenship to become believers. Instead, the faith of these Christians continued to spread within their pre-existing communities despite persecution.

Paul also showed us the way to spread the gospel across religious barriers when he did not denounce Greek philosophy (Acts 17) or the gods and goddesses of the Romans (Acts 19) but instead taught new believers to remain in their families, communities, and people groups (1 Cor 7:17, 20–24). Their community of belonging was not changed, only what they were putting their faith in. They were not saved by “becoming Christians” but by having faith for salvation in the Lord Jesus, by believing the message of the gospel.

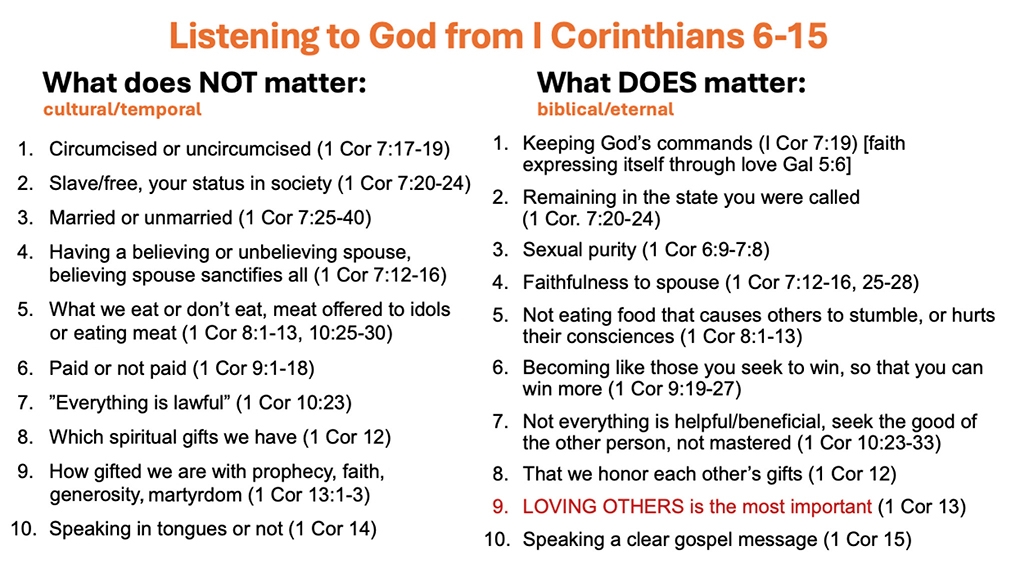

Paul made clear that what was of utmost importance was the saving gospel message: “That Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day… this is what we preached and this is what you believed” (see 1 Cor 15:1–11). This gospel message is the same for every people group. In fact, Paul spends ten whole chapters in 1 Corinthians (chapters 6–15) clarifying which things matter and which do not, when a person is coming to faith from within a different religious community (see Table 1). Paul gave us all an example of how to listen to God when communicating the gospel message into an idolatrous society or another established widespread religion.

In 1st Corinthians, Paul wrote that it did not matter if people were circumcised, slaves, married, had a believing spouse, ate meat sacrificed to idols, nor whether they were paid to spread the gospel. It also did not matter whether they had spiritual gifts (and what kind), whether they had faith (and how much), nor if they generously gave to the poor. What did matter was whether they were transformed, born again as a new creation (Gal 6:15–18), obedient to God (1 Cor 7:19), sexually pure, faithful, not hurting or causing others to stumble, not mastered by anything, honoring the gifts God gave others, speaking a clear gospel message, and above all else—loving others (1 Cor 13, Gal 5:6).

God’s Plan for Blessing, not Replacing, Communities and Family Households

The church was never intended to replace one’s natural family and community. The New Testament shows us over and over again how to bring the good news message without pulling people out of their families or people-group identities, including the socio-religious identities of the rest of their people group. The followers of “the Way” (what the Jewish believers were called in the New Testament) continued to be part of the non-believing Jewish community for centuries. Sociologist Rodney Stark points out in Chapter 3 of his book The Rise of Christianity that the gospel spread through both the Jewish and the Roman social networks precisely because it retained “cultural continuity” in both cases, allowing the believers to retain a significant amount of their original cultural heritage. We know that believers continued to be considered part of their own religious communities if they could be buried in their community cemeteries. And Stark points out that Jewish cemeteries contain people buried with signs of faith in Christ for nearly 300 years after Christ.2

But, as Stark also points out, when the Roman Empire stopped persecuting Christians, the Roman and Greek Christians began to denounce Jewish believers for continuing to follow the Jewish religion and for staying in their Jewish communities alongside many who refused to acknowledge Jesus as the Messiah.3 The movement of faith in Jesus as their messiah within the Jewish communities slowed to a stop when the Gentile Christians essentially forced Jewish believers to leave their Jewish communities with their religious practices, and join Roman or Greek communities, complete with Roman and Greek ways of following Jesus—many of which were unnecessary and some syncretistic. (For example, the Roman Christians increasingly adopted Roman religious hierarchical structures, with empire-funded priests, while the Greek Christians brought in the constant philosophizing and theologizing of the Greek religious culture, triggering the theological battles, anathemas, and creeds. Both Greek and Roman Christians substituted Mary, the mother of Jesus, for the “mother goddess” pagan figures and began calling her the “Mother of God.”)

There is long biblical history of God saving and working through whole households, notably the hundreds of men in Abraham’s household being circumcised because of his faith, and God’s covenant to bless all the families of the earth being reiterated to each of his descendants. This pattern is repeated throughout Scripture, as listed in the Mission Frontiers (Sept/ Oct 2018) article “The Oikos Hammer” by Steve Smith. Paul understood this principle when he told the Philippian jailer, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved—you and your household” (Acts 16:32). In Luke, Jesus told the disciples he was sending out to evangelize to look for a “person of peace”—someone who would invite them in to stay and share the gospel with his whole household (Luke 10). In this way, a person of peace (while still an unbeliever) brings a blessing onto his or her family (1 Cor 7:14–16). And Peter teaches that by remaining in their homes and living godly lives, believers can win non-believing family members to the Lord without even speaking any words at all (1 Pet 3:1). Rodney Stark credits the continuous expansion of the gospel throughout the Roman empire to “open networks” in which believers continued to participate with their non-believing families and communities, including marrying non-believers.4

In conclusion, we see that God’s plan throughout the ages is to win whole families and communities to himself, thereby “blessing all the families (ethne) of the earth.” He never intended the “church” to replace the family or community, even in the most difficult situations.

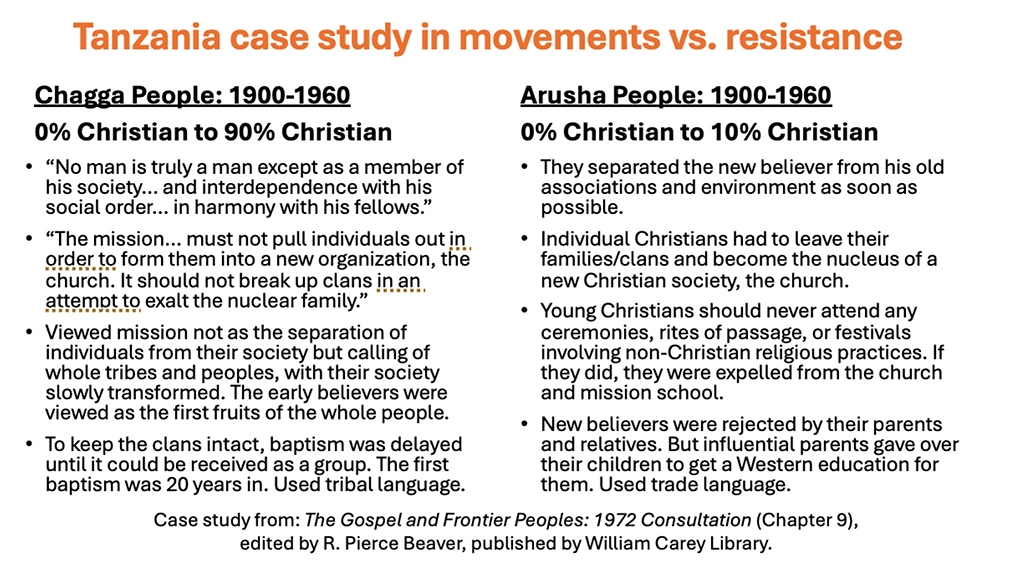

The gospel was a message brought into households and communities, which when received by faith resulted in salvation coming to some and blessing coming to all. This plan was modeled by Jesus and the apostles, and missionaries throughout the ages, when they brought the gospel message into very different communities, including religious ones (see Table 2 above).

With the remaining people groups untouched by the gospel (the Frontier People Groups, mostly Muslims and caste Hindus), we must seek to diligently copy the apostles and missionaries who successfully brought the gospel message into the families and communities of other religious blocs. Even if their family is trying to ostracize them, we must not seek to replace the family of new believers by attracting them to other cultural expressions of Christianity as a “new family.” If we do the latter, these people groups will continue to be completely unreached. Instead, we must bring the gospel message into their households, as Peter did with the household of Cornelius, a Roman centurion, and the coming of the Holy Spirit upon them will confirm that God has accepted their faith, even as he accepted ours.

1 For a deeper dive, look at the Nov/Dec 2018 (40.6) and Mar/Apr 2024 (46.2) issues of Mission Frontiers magazine.

2 Stark, Rodney, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1988), 49–55.

3 Stark, 55–70.

4 Stark, Rodney, 55–57.

Author

RW LEWIS

RW Lewis wrote “a church for every people” in her Bible in 1980 and has worked toward that goal with her husband, Tim, ever since, helping to found the USCWM/FV, Frontiers, and Telosfellowship.org.

Scripture references are taken from the NIV.

Subscribe to Mission Frontiers

Please consider supporting Mission Frontiers by donating.

Subscribe to our Digital Newsletter and be notified when each new issue is published!