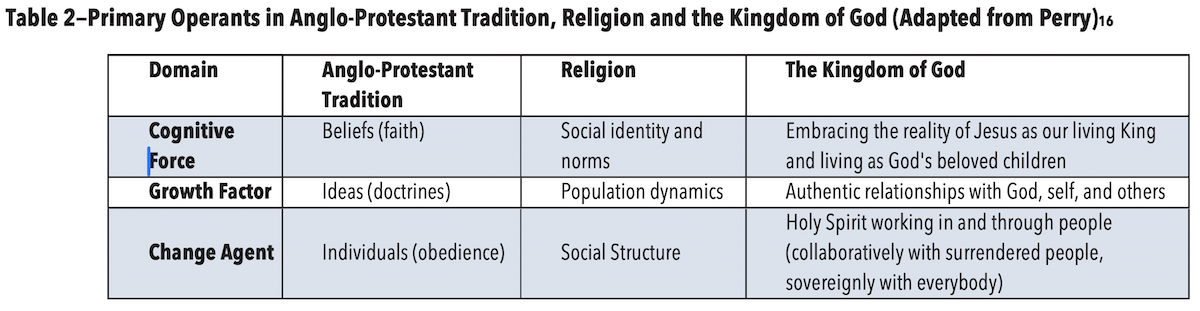

Samuel Perry’s Religion for Realists makes an important contribution by arguing for religion’s real-world significance. He challenges assumptions about what drives religious growth which he says are grounded in the Anglo-Protestant tradition, arguing that these “operants” are actually driven primarily by human factors, summarized in the table below.

Contrary to the rhetoric of the “Anglo-Protestant Tradition,” beliefs (faith), ideas (doctrines), and individuals (obedience) are not the primary forces at work in the health and growth or otherwise of religion. What really matters are social identity and norms, population dynamics and social structure.2 He seeks to persuade academics and policy makers in the USA to take religion seriously as something that needs to be understood rather than ignored or sidelined.

He raises legitimate questions about religion and the Anglo-Protestant tradition in US society. However, his framework, while sociologically sound, does not allow for divine agency. For those of us concerned with following Jesus, participating with God in missio/motus Dei and helping others take the same journey, the table is inadequate, and to focus on either column would have important downstream implications for discipleship and evangelism, among other things.

I’d like to propose a revised and supplemented version of his table in the hope that it will build on the conversation he has started and be of use to those seeking to follow Jesus and help others do the same.

To do this, I’ll first review the invitation extended by Jesus and Paul in the Gospels and Acts as a New Testament reference point for religion and religious growth. Then I’ll look at each of Perry’s operants, before wrapping up with my proposed amendment to the table above.

The New Covenant Is Not a Religion

Jesus and Paul proclaimed something fundamentally different from “religion” as described by Perry.

Jesus’ gospel concerned the kingdom of God, the living and active reign and rule of the Father. “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand” (Mark 1:14–15).3

Jesus called people to repent and believe the gospel—that God’s reign was now accessible in a new way. What did that mean?

This meant accepting Jesus’ authority and adjusting life accordingly. At Pentecost, God’s presence was made directly available to “all flesh”—embracing the kingdom continued to mean accepting Jesus’ authority, now also mediated through direct access and relationship with the Father by the Spirit.

Jesus expected people to walk in direct relationship with God. In John 14–17, he describes the role of the Holy Spirit after his departure through whom he expected all his disciples to have access to God (John 14:16–17, 15:7–11). He expected that the Spirit would directly guide, instruct, and teach (John 14:26, 15:26, 16:7–15). This is in keeping with the Gospels’ depiction of Jesus’ relationship with the Father, and many of the Old Testament prophetic pictures of God’s ultimate goal (e.g. Jer 31:33–34, Joel 2:28–29), not to mention the original picture we see in Genesis 1–2.

Jesus’ gospel was not merely to adopt a new belief about the world, but to embrace the reality of God’s reign and rule personally by relating to him in a new way—first through the Messiah, and then through the Holy Spirit in light of the Messiah’s death and resurrection.

Paul holds the same expectation.

For example, in Galatians he paints the picture of the Messiah replacing the tutor of the Law, bringing legal minors to full sonship4 and enabling a life of direct relationship with and submission to the Holy Spirit.5 It is noteworthy that for these former pagans, now disciples, he appears to place pagan culture and Jewish religious culture on the same level in

the post-Messiah, post-Pentecost unfolding of God’s kingdom—to submit to the Jewish religious tradition was to revert to the “same worthless principles” they formerly submitted to (Gal 4:8–11). In contrast, he expects that if they “walk by the Spirit” this will outflow in transformed relationships (Gal 5:16–26).

So, Jesus and Paul are both clearly announcing and expecting something new and distinct from the existing social order, and external to humans and human society—namely, the reign and rule of God expressed dynamically through communication between God and people.

Both demonstrated this kind of relationship personally and appeared to expect it would be part of the new reality for those who accepted their message.

Social Dynamics Are Primary Drivers for Religion, Not the Kingdom

As we discussed earlier, Perry highlights three “primary operants” in religion, and contrasts Anglo-Protestant rhetoric with what he asserts is truly important in religion.

While Perry’s table may be sufficient for describing religion and the Anglo-Protestant tradition, it appears to be insufficient for describing the kingdom of God that Jesus and Paul proclaimed.

There are clear indications that Jesus and Paul were aware of the operants that Perry highlights, and that they leveraged them in the way they sought to spread the good news and invite people into it. However, it is equally clear that these operants are unable to fully describe the impact of their ministry—the kingdom of God cannot be reduced to either the Anglo-Protestant tradition or Perry’s “Religious Reality.”

Our space here is limited, but let’s take a brief look at each of Perry’s “primary religious operants,” some ways each driver connected with Jesus and Paul’s practice, and potential implications for our own missional engagement.

Operant 1: Cognitive Force

Perry argues that social belonging, not belief or doctrine, holds religious groups together. Knowing “our tribe” motivates religious alignment more than faith content.6 The content of belief is not so important as who else shares it. The cognitive force is relational.

Jesus and Paul recognized this insight, as do many modern mission practitioners.

Jesus appears to have prioritized his time and energy with “the lost sheep of Israel” as his primary (though not exclusive) focus (Matt 15:21–28). Paul’s recurring strategy was to go to the synagogues in the cities he visited (Acts 14:1, 17:1–2). Where there was no synagogue, Paul sought out places he knew that Jews and God-fearers would gather (Acts 16:13). In these places, he knew he would find people—Jewish and non-Jewish—who were drawn to the God of Israel, were familiar with his story and character, and valued the Hebrew Scriptures as a source of authority.

Furthermore, they adjusted their approach to different groups,7 engaging and inviting those groups to respond to the accessibility of God’s kingdom in ways that resonated with their “belonging group.”

Social belonging was a concept that informed Jesus and Paul as they engaged different communities, determined focus and strategy, and what and how they communicated with them.

However, the gospel message proclaims new information about God, people, and our relationship to each other. It invites us to embrace a new belonging structure in the light of who God says he is and who he invites us to be. What held these new communities together was not primarily beliefs but a shared identity of people relating to God, belonging to the Messiah, and seeking his will in their lives.

For those accepting the gospel, the new relationships tended to reduce rather than increase the status of participants, and it often led to tension and conflict with established belonging groups—Jewish and Roman.

The example of Jesus and Paul suggests that the relational implications and substance of the gospel were more significant than just doctrinal beliefs or social belonging.

Operant 2: Growth Factor

Perry recounts an “Anglo-Protestant pop culture story of how Christianity grew throughout history” which he believes heavily (and wrongly) emphasises the transformative importance of ideas.8 Leaning heavily on examples in the US, he argues that population dynamics drive religious growth. Others have previously explored this dynamic in relation to the Roman Empire,9 and while there are indications that population dynamics may have played a part in long-term growth once disciples reached a critical mass in the wider population10 this does not appear to have been the case in the early stages we see in the Gospels and Acts.

Jesus and Paul were operating in social environments where few initially agreed with or understood them. It’s difficult to be categorical about what drove the growth in response to their message, but we can confidently say it was neither population dynamics—the timeframes of change were simply too short—nor mere ideas.

They weren’t asking people to agree with an idea about the kingdom of God but to embrace its reality. They were inviting people to a new way of relating to God, the world, and each other. They personally embodied and lived out that invitation, and they appeared to expect those who responded to their message to do the same.11 Interestingly, recent research of unchurched Australians who began following Jesus as adults points in a similar direction.12 In large part, the change in their lives was precipitated by exposure to people who embodied strikingly authentic relationships with God, themselves, and others, and invited them to participate.

Where implicit acknowledgement of population dynamics is significant is in the importance of sowing that embodied relationship into different cultural contexts. Jesus was focused on Israel, but his interactions with people from other communities indicate deliberate desire to have them understand and embrace this new relationship in their own context (John 4:5–26, Mark 5:1–20). Paul, too, was explicit in his intention to enable people to experience this new reality with God in their own cultural and social context. How would Gentiles across the Mediterranean world truly grasp what life with Christ entailed if they only ever saw it in a Jewish cloak? Hence, he sought to embody life with Christ in a Jewish way amongst Jews, and in a Gentile way amongst Gentiles to effectively communicate the reality of the gospel where they were so that it might spread through their context (1 Cor 9:19–23).

Ideas and population dynamics are both significant, but Kingdom growth appears to take place primarily through the impact of authentic relationships with God, self, and others.

Operant 3: Change Agent

For his third operant, Perry discusses change agents. He contrasts the idea of an individual or group being the primary change agent in the Anglo-Protestant tradition with what he calls the realistic view in which social structures are what make the difference. In this regard, he deals mainly with the impact of government policies and religious pluralism, which serve to weaken religious affiliation.13

Perry’s arguments deal primarily with macro structures. These things certainly impact people and religion, but are they the primary drivers of change in the kingdom of God?

Jesus and Paul show awareness of these broader structures in their commands to pray for government and emperor but appear to be more concerned with what we might call “micro” structures.

Within the field of Jesus’ assignment, he intentionally visited and sent ambassadors to the different villages in the region (e.g. Luke 9:1–6, 10:1–12). As he does this, Jesus gives detailed instructions on operating within the “micro” social structures of individual villages. To reach a village, find a household. To reach a household, find an open individual who is sufficiently influential in their immediate relationships to cause that household to be opened to you. Jesus recognized and respected the authority of gatekeepers within social networks and trained his disciples to do the same. Communicate clearly, warn, if necessary, but don’t fight. Submit to their authority.

Jesus gives clear instructions that consider social structures and realities in village settings and appear to have been effective then and are proving equally effective in similar social settings in the 21st century.14

Paul followed a similar pattern in Acts as he looked at the wider Roman world—visiting key cities, looking for open social structures and serving them where he found them. Once established, he appeared to assume that social structures would do their work, as transformed disciples in the major urban centers impacted their neighbors and those in surrounding regions.

We see that Jesus and Paul were aware of social structures and worked with them, but those structures were wineskins for the kingdom rather than the agent of change. The choices of individuals were significant, but Jesus and Paul appeared to expect the Spirit of God to drive change as he interacted with individuals and communities.15

The change agent for the kingdom of God is the Holy Spirit, working collaboratively with individuals who had received the gospel, surrendered themselves to God’s authority, and embraced their identity as his children (and working sovereignly through everybody else).

Suggested Alternative & Application

Here’s my suggestion for building on Perry’s hypothesis including the kingdom of God: See Table 2 above.

Distinguishing the kingdom of God (and his activity as a living Person) from religion clarifies important missiological questions.

• What does God invite us into? What does it mean to take hold of it ourselves? Have we taken hold of it?

• What are we transmitting to others? What exactly is our evangelism inviting people into?

• What is the goal of our discipleship processes? What are the outcomes of our discipleship processes? To what extent are they aligned with God’s kingdom?

• Are we merely drawing people into our culture (social identity and norm, social structures) or are we helping them embrace a spiritual reality? Is God’s personal and direct involvement necessary for them or optional?

These questions are important in any context, but particularly in cross-cultural ministry.

Conclusion

For those of us concerned with missio Dei and motus Dei, understanding religious dynamics helps us discern between religious structures and God’s kingdom. With this distinction, we can have greater confidence that we are sowing good gospel seed, while also stewarding social dynamics appropriately and in service of the Father’s purpose.

Where Perry’s discussion of religion is particularly relevant to us is this: The religion that he describes can function entirely without God’s direct and personal involvement and fails to acknowledge or capture the essence of what Jesus and Paul were announcing and inviting people into. God’s personal and direct involvement were hard-baked into their invitation and process—first, in and through Jesus Christ as he trusted and obeyed the Father, and subsequently, in and through the Holy Spirit.

1 Perry, Samuel L. Religion for Realists: Why We All Need the Scientific Study of Religion, Kindle (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 10.

2 Perry, 4.

3 It’s also noteworthy that "the kingdom of God" was a significant part of Paul’s theology (Rom 14:17, 1 Cor 4:20, 6:9–10, 15:24, 15:50, Gal 5:21, Eph 5:5, Col 1:13, 4:11, 1 Thess 2:12, 2 Thess 1:5) and that Luke concludes Acts with Paul continuing to proclaim the kingdom of God (Acts 28:31).

4 A reference to legal status and honor, rather than gender.

5 There are a range of views regarding the relationship of the Law to followers of Jesus under the New Covenant which I don’t have space to engage with here. One overview is available in Greg L. Bahnsen et al., Five Views on Law and Gospel (Zondervan Academic, 2010).

6 Perry, 41.

7 Compare Jesus’ audience and message in Mark 1:14–15, John 3:1–21 with John 4:1–26. Compare Paul’s audience in Acts 13:14–41 with Acts 14:8–18 and 17:22–31. Note, also, the explicit description of his approach in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23.

8 Perry, 71.

9 Stark Rodney, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries, 1st ed. (Harper Collins, 1997), Rodney Stark, Cities of God: The Real Story of How Christianity Became an Urban Movement and Conquered Rome, 2st ed. (HarperSanFrancisco, 2006).

10 Stark, The Rise of Christianity.

11 e.g. Jesus—John 15:1–25, Paul—1 Cor 4:16–17, 11:1, Phil 3:17, 4:9.

12 Lynne Taylor, “Toward Relational Authenticity: The Experience of Atonement in Christian Conversion Today,” Colloquium: The Australian & New Zealand Theological Review 49, no. 1 (2017): 31–47; Lynne Taylor, “Our Doing Becomes Us: Performativity, Spiritual Practices and Becoming Christian,” Practical Theology 12, no. 3 (2019): 332–42, doi.org/10.1080/1756073X.2019.1595317; Lynne Taylor, “A Multidimensional Approach to Understanding Religious Conversion,” Pastoral Psychology 70, no. 1 (2021): 33–51, doi.org/10.1007/s11089-020-00934-1.

13 Perry, 99.

14 Victor John, Bhojpuri Breakthrough: A Movement That Keeps Multiplying, Kindle, with Dave Coles (WIGTake Resources, 2019); Aila Tasse and Dave Coles, Cabbages in the Desert: How God Transformed a Devout Muslim and Catalyzed Disciple Making Movements among Unreached Peoples, Kindle (BEYOND, 2024); Aychi B.R. and Dave Coles, Living Fire: Advancing God’s Kingdom in Challenging Places, Kindle (Beyond, 2025), www.amazon. com/dp/B0DTC2SQSX.

15 e.g. John 14:25–26, 15:26–27, 16:7–11, Acts 1:6–8, Philippians 2:12–13.

16 Perry, Religion for Realists: Why We All Need the Scientific Study of Religion, 10.

Author

S CRAWLEY

S Crawley is part of the Urban Wheat Project team, serving indigenous teams who are called to serve brokenness and lostness and seed viral discipleship in Asian cities. urbanwheat.org/blog

All Scripture references taken from the ESV.

Subscribe to Mission Frontiers

Please consider supporting Mission Frontiers by donating.

Subscribe to our Digital Newsletter and be notified when each new issue is published!